Slippery slope: Climate change is melting away skiing business – how Whistler Blackcomb innovates to stay ahead of the slush

Blackcomb Whistler illustrates what adaptation strategies ski area operators can employ to react to recent climate change developments

The UNEP has cited the winter tourism industry – particularly the ski industry – as one of the most vulnerable industries to the impacts of climate change [1].

To name only a few examples of the effects of the global warming, ski area operators are experiencing decreasing areas of snow cover, less snowfall, melting glaciers, and shorter snow seasons. According to the Climate Change Report of the IPCC, the snow cover area in the Northern Hemisphere during March-April is expected to decrease every decade by 1-2% [2]. Simultaneously, the snow season is expected to be shortened by more than 5 days every decade [2].

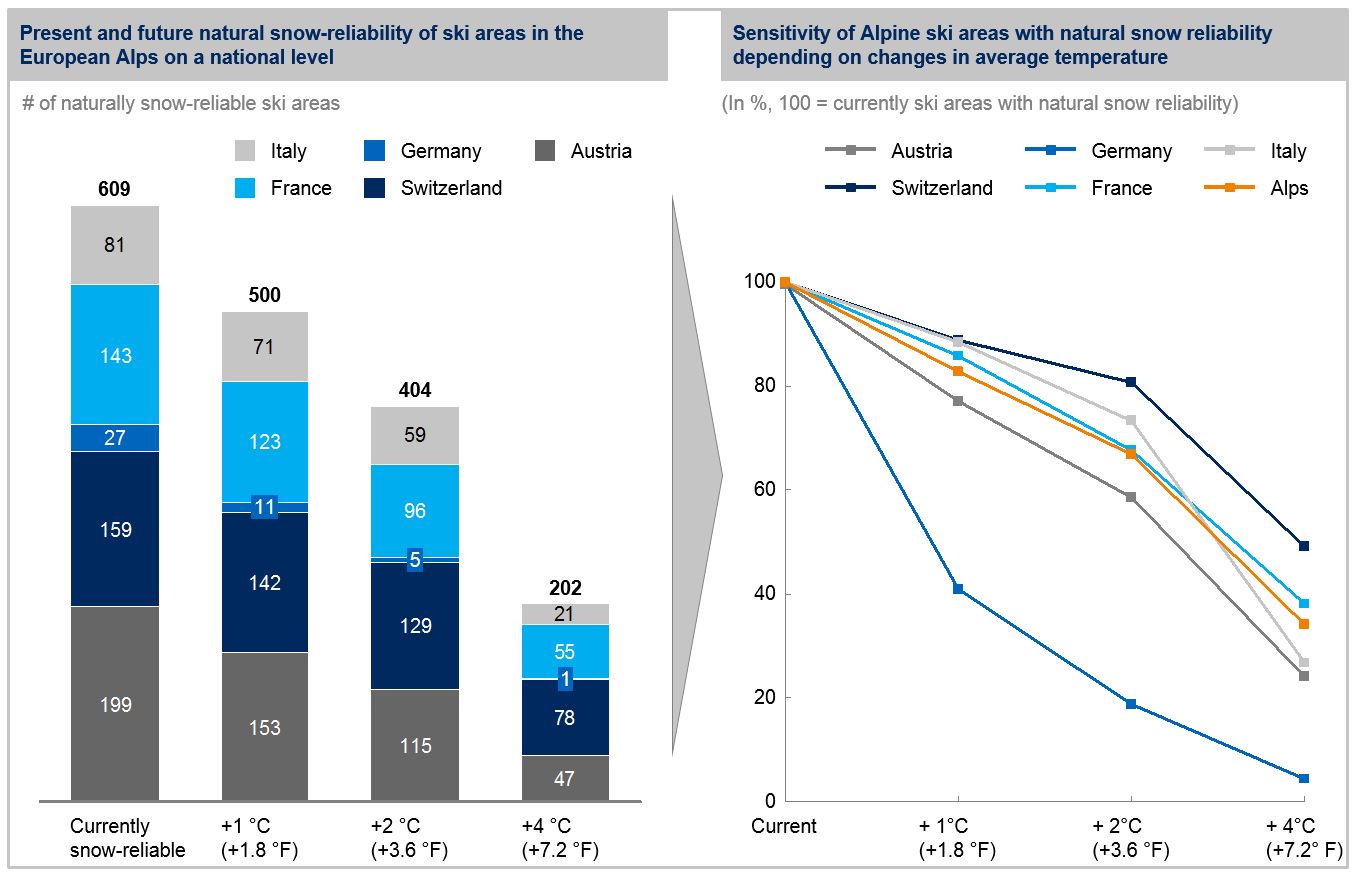

These alarming figures become even more worrisome when considering the direct implications this can have on the ski industry. Exhibit 1 shows the effects of rising temperatures on the future natural snow-reliability of ski areas in the European alps [3]. Even if it would be possible to limit the global warming to 2° C (3.6° F) by 2050, the number of naturally snow-reliable ski areas would drop by 34% from 609 to 404 with Germany being the most sensitive of the countries in the European alps region (>80% drop) [3].

Exhibit 1: Own illustration, derived Abegg et al. [3]

Exhibit 1: Own illustration, derived Abegg et al. [3]

The outlook in the U.S. is unfortunately comparably drastic: “Without intervention, winter temperatures are projected to warm an additional 4 to 10 degrees Fahrenheit by the end of the century […]. Snow depths could decline in the west by 25 to 100 percent. The length of the snow season in the northeast will be cut in half.” [4]

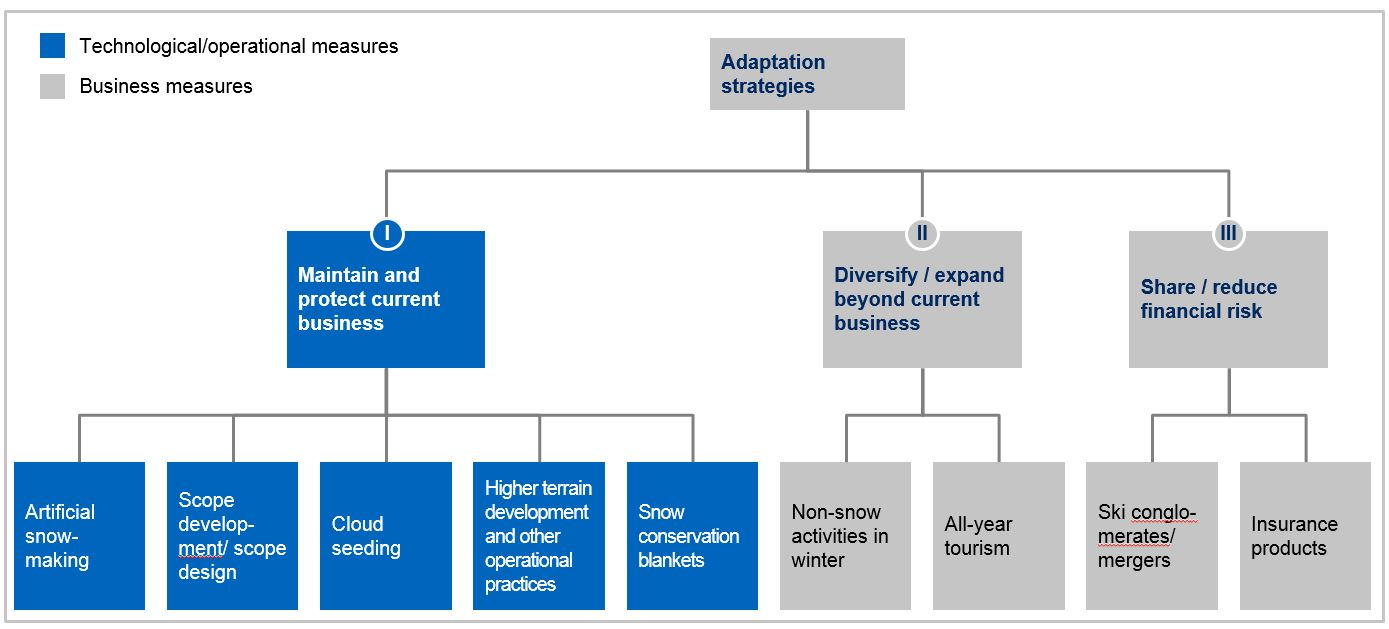

Ski area operators can follow multiple corporate adaptation strategies leveraging various technological and business practices to react to recent climate change developments.

The different adaptation measures can be subsumed under 3 main strategies, of which Whistler Blackcomb (WB) applies all of them. They are summarized below in Exhibit 2.

Exhibit 2: Own illustration, derived from Hoffmann et al. [5], Elsasser & Bürki [6], and Scott & McBoyle [7]

Exhibit 2: Own illustration, derived from Hoffmann et al. [5], Elsasser & Bürki [6], and Scott & McBoyle [7]

I. Maintain and protect current business

When remaining within the current business, ski area operators apply various technological measures to react to the developments initiated by climate change. The most familiar climate adaptation is the use of artificial snow machines. Although snowmaking can entail huge investment and operating costs (~US$ 600,000 investment costs + US$ 18,000-30,000 annual operating costs per kilometer of ski-slope [6]), economic benefits often outweigh the high costs by extending the average ski season by 55-120 days [7].

Other secondary adaptation measures include:

- slope development to contour and prepare slopes in a way that reduces the minimum required snow to operate

- cloud seeding as applied in some ski resorts in Colorado to produce additional precipitation, however with mixed results so far [7]

- higher terrain development & other operational practices such as the gradual transfer of ski areas into higher terrain, shift to north-facing areas, or even the deployment of dry slopes

- snow conversation blankets made out of fleeces to protect glaciers in the summer for earlier season openings such as often seen in Austria (e.g. Stubaier Gletscher [8])

WB provides one of the most technologically advanced snowmaking systems with over US$ 60 million invested in >270 snow guns fed by 3 reservoirs and more than 40 employees working around the clock to oversee the snowmaking [9]. As climate change progresses, snowmaking machines are being installed in higher elevations. Just recently, WB has started to install machines on the Horstman Glacier at above 2,000 meters of elevation [10].

As one of the pioneers in operating ski areas in the Northern-American region, WB also recently started to deploy glacier blankets on the Horstman Glacier to improve summertime snow retention [11].

II. Diversify / expand beyond current business

Some ski area operators choose to decrease their vulnerability to climate change by diversifying their revenue streams to areas that are not negatively affected by the global warming [5].

Also here, WB is reacting faster than many other ski area operators and has recently launched a US$ 345mn investment plan that includes an enormous indoor waterworld, biking & hiking trails, and luxury accommodation to diversify its revenue streams [12].

III. Share / reduce financial risk

A different strategy is to reduce overall financial risks by either directly purchasing snow or temperature insurances or by merging/cooperating with other ski areas. This increases capital and marketing resources and significantly decreases vulnerabilities through regional diversification (ski conditions can vary significantly even at nearby ski regions).

Here again, WB became active early on by combining the Whistler area with the Blackcomb area through the Peak 2 Peak gondola to provide access between two ski areas without having to go down to the base where snow levels are much lower [11].

Additionally, WB just received a friendly takeover-offer from Vail Resorts over US$ 1.4bn that could further drive the consolidation of ski area operators.

Concluding, WB showcases how ski area operators can use adaptive measures to react to the expected drastic developments. If this however proves to be sufficient, is yet to be seen.

Word count: 791 (excluding citations and exhibits)

Footnotes:

[1] J. Dawson & D. Scott, “Managing for climate change in the alpine ski sector,” Tourism Management 35, (2013): 244-254, ScienceDirect, accessed October 2016.

[2] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, “Climate Change 2013 – The Physical Science Basis,” Climate Change Report (2013), IPCC, https://www.ipcc.ch, accessed October 2016.

[3] B. Abegg, S. Agrawala, F. Crick, & A. De Montfalcon, „Climate change impacts and adaptation in winter tourism,” Climate Change in the European Alps (2007), OECD, http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org, accessed October 2016.

[4] E. Burakowski & M. Magnusson, “Climate Impacts on the Winter Tourism Economy in the United States,” Climate Impact Report (December 2012), NRDC, https://www.nrdc.org, accessed October 2016.

[5] V.H. Hoffmann, D. Sprengel, A. Ziegler, M. Kolb, & B. Abegg, „Determinants of corporate adaptation to climate change in winter tourism: An econometric analysis,” Global Environmental Change 19, (2009): 256-264, ScienceDirect, accessed October 2016.

[6] H. Elsasser & R. Bürki, “Climate change as a threat to tourism in the Alps,” Climate Research 20, (2002): 253-257, Inter-Research, accessed October 2016.

[7] D. Scott & G. McBoyle, “Climate change adaptation in the ski industry,” Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies in Global Change 12, (2007): 1411-1431, Springer, accessed October 2016.

[8] Stubaier Gletscher, “Glacier Protection in the Ski Area,” https://www.stubaier-gletscher.com/en/stubai-live/news/glacier-protection, accessed October 2016.

[9] Pique, “Whistler’s $60-million snowmaking system opens the slopes, saves the holidays,” http://www.piquenewsmagazine.com/whistler/whistlers-60-million-snowmaking-system-opens-the-slopes-saves-the-holidays/Content?oid=2542381, accessed October 2016.

[10] CTV News, “Whistler to test snowmaking on glacier to fight climate change,” http://bc.ctvnews.ca/whistler-to-test-snowmaking-on-glacier-to-fight-climate-change-1.2425092, accessed October 2016.

[11] The Tyee , “Peak Snow? BC Ski Resorts Brace for Warmer Era,” http://thetyee.ca/News/2014/12/22/Peak-Snow-Ski-Resorts, accessed October 2016.

[12] CBC News, “Whistler Blackcomb tables $345M development plan,” http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/whistler-blackcomb-renaissance-plan-1.3522817, accessed October 2016.

These are really interesting findings on ways that ski resorts can reduce risk associated with less snow.

One thing I’d further dive into is whether these practices in snow machines are truly sustainable. From my own research, snow machines are actually not environmentally-friendly and require immense amounts of water and electricity to operate. By investing in over 270 snow machines, what is WB’s environmental impact? Do they care?

One article that you may be interested in reading is: http://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/8/9/851

In the article, Environmental Management and Sustainable Labels in the Ski Industry: A Critical Review, it breaks down how ski resorts could be focusing on having more sustainable practices to reduce environmental impact, rather than resorting to more damaging practices (such as snow machines).

I do like the idea of diversifying into other areas. Especially in California, I’ve noticed ski resorts focusing on more summer activities to try to counter-balance the reduced ski season.

Having learned to ski on the Whistler slopes as a kid, this was a fantastic read – thanks RM. I agree Whistler has pursued multi-pronged approach to protect its operations, most aggressively via artificial snowmaking (a huge perk of hosting the 2010 Olympics, which I believe contributed roughly a third of the $60M investment to date) and off-season, or year-round tourism boost. Karla does raise an interesting point – beyond these “Band-Aid” solutions to sustain ski resorts, how can we address the root cause, i.e. how can we make ski resorts more environmentally-friendly in the first place? Is it a sustainable practice to let individual ski resorts pump hundreds of gallons of water per season through artificial snowmaker machines, and what types of new technologies / new types of slope contours are available to minimize water/snow consumption? Should governments get involved to regulate number/type (i.e. cleared versus graded ski runs) of new ski resort developments that might damage the natural ecosystem?

Thanks RM for a comprehensive look at how Whistler Blackcomb is responding to changing conditions. I would be curious to hear your thoughts on what changes Vail Resorts might implement after acquiring WB and whether you think they would engage in more or less sustainable practices? Also would be interesting to hear your take on what opportunities Vail / WB should look at to continue to consolidate the industry and whether they are better off sticking with acquiring resorts in North America or if they should look to Europe or other regions?

Interesting blog! I can’t help looking at this problem through a more scientific lens though…

Even if using an artificial snow machine does make financial sense because it lengths snow season for 55-120 days, I see it is a vicious cycle. I imagine it takes a lot of electricity to fuel an artificial snow machine to cover large parts of a slope, if not the entire slope, or to thicken the snow on a slope. More electricity usage, more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, a warmer atmosphere, less snow, more need to use the artificial snow machine! Additionally, before investing in an artificial snow machine, I would want to know how I can prevent the artificial snow I’ve created from melting any time soon…thus preventing me from having to pull out my artificial snow machine again, or just keep it going constantly, and adding to my utility bill.

I admit that creating artificial snow and thus, creating an environment on a ski resort is like creating an artificial environment in an office or residential building- heating during the winter, cooling during the summer. However, I would argue that there is no way to insulate snow on a mountain and stop it from melting, unless we use ‘glacier blankets’- what are these? There are ways to insulate building to retain their heat for longer. I just don’t see artificial snow machines as sustainable, either in the financial or environmental sense. I think WB should diversify their investments and become a water park 🙂

Thanks for the post! I’ve been following Vail Resorts’ acquisition activity for several years. To @eross’ question: they have partnerships set up with several resorts in France, Switzerland, and Austria (and the list is growing!). I too have wondered how they will leverage this market power — each year, lift ticket prices appreciate considerably. Their sustainability efforts to date seem limited to mountain operations: The company is currently pursuing a 10% energy reduction by 2020, and investing in technology for grooming, snowmaking, and solar power (http://www.vail.com/mountain/environment.aspx#/EnergySavingsTab). However, Vail Resorts’ typical approach also involves real estate development and a significant associated carbon footprint. They often own a considerable portion of real estate — retail and residential — at the base of each resort they operate (and the mountains are often set up as long-term leases from national parks vs. ownership). I wonder if they can learn something from our classmates’ commentary on the hospitality industry — e.g., LEED certification, “make a green choice,” waste reduction, and more in how they operate their buildings.

I think this is one of the few effects of climate change that many of us can directly relate to. In my native Romania, where slopes are built at lower altitudes, it happens more and more often that we do not get enough snow until February or sometimes for an entire year. And I can clearly remember this not being the case when I was a child. To echo MC’s point however, I am a bit frustrated with the solution we have decided to adopt. Our measure of creating artificial snow is not only not fighting against the root of the problem, but actually exacerbating it. One option to partially mitigate the problem could be charging an eco tax in order to fuel the artificial snow production from renewable energy sources (or of course, the equivalent green certificates). While I know this would not totally address the issue, it can be a step forward, and I would expect the skiers’ willingness to pay to be higher than the average consumers’.