Outsourcing Chores: Groceries On Demand

Exploring how digital delivery has made the grocery channel accessible to busy consumers who need to eat, and are willing to pay a premium for fresh food.

“Each wave of change doesn’t eliminate what came before it, but it reshapes the landscape and redefines consumer expectations, often beyond recognition. Retailers relying on earlier formats either adapt or die out as the new ones pull volume from their stores and make the remaining volume less profitable.” – Darrel Rigby “The Future of Shopping” Harvard Business Review December 2011

Who has time to grocery shop with all of these HBS cases to read? – a common complaint among students slogging through their first RC semester.

Thankfully for HBS students, and for many consumers, the digitization of the grocery shopping experience has created a way for store bought goods to be delivered right to your door. For a fee and a few minutes of virtual shopping, consumers can skip the trip to the store, and stock their fridge with food for the week!

There are many competitors within the digital grocery delivery space (ex: AmazonFresh, Peapod, Instacart, Safeway). Some rely on their own warehouses of goods, others are run by and for specific retailers, with others still providing access to specific retailers through personalized shoppers. Instacart is one of the latter category. In Instacart’s model, the consumer places orders for particular stores through Instacart’s smartphone app or website (4). Once the order is received, an Instacart shopper goes to the store, picks out and purchase your products, then delivers the items to your home (3). Similar to Uber, the Instacart shoppers are “independent contractors” and not provided benefits like healthcare (3). However, these shoppers can earn between $15-$30 per hour, are able to work flexible schedules, and not required to hold a college degree (3).

On the other side, Instacart is making money through delivery fees (flat rate and peak pricing), product markups, and through partnerships with CPG manufacturers (3). CPG companies can partner with Instacart to offer free delivery, or other deals, to consumers who purchase their products. For example, if you buy $20 worth of Ben & Jerry’s ice cream this week from Whole Foods, you can get free delivery worth 5.99-7.99 (4).

Source: Instacart Website

While other grocery delivery models rely on substantial warehousing, delivery trucks, full-time staff to pack and distribute deliveries, and significant start-up investment, Instacart side steps all of these factors by contracting out the delivery and picking to their shoppers and relying on the grocery stores for inventory (3).

For the consumer, the main value proposition is convenience. Instacart digitized the grocery shopping experience by creating an app and website organized by department, key word, recently purchased, and best deals (4). Consumers can use the search when they know exactly what they want, instead of having to browse aisles as they would in a traditional store. The “recently purchased” section allows consumers to access previous purchases further speeding up shopping (4). To smooth out the online shopping process, Instacart does a few things. When checking out, consumers indicate what to do if items are out of stock: either swap it for a comparable good or shoppers will leave items out (4). While the shopper is at the store, they may also contact the consumer to check and see if they have any questions about the order specifications (4). All of these features add convenience for shoppers and help increase consumer confidence that they will be satisfied with the entire experience.

What Should Instacart Do Next?

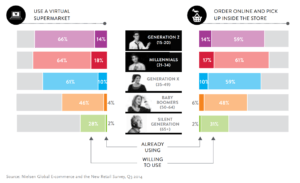

Grocery delivery has been moderately successful penetrating younger demographics, specifically Millennials and Generation Z, who have grown up in the digital landscape; but the industry has yet to appeal more broadly to Baby Boomers and Generation X (1). Given that these groups still represent the majority of the US population (5), companies like Instacart should consider how to get these consumers on board with buying their groceries online. Education and increasing trialability are two factors they should consider when targeting pre-Millennials consumers who are more hesitant to give up their habitual weekly trip to the store.

In addition, Instacart should consider what products are best suited for digital delivery services. According to Nielsen’s market research, some products are stronger drivers of ecommerce purchases while others present barriers (1). For instance, items bought on a stock-up trip (ex: soap, personal care products) and products that have a high price-to-weight ratio items (ex: baby wipes) are strong fits for ecommerce (1). Other products which you may need urgently (ex: pain medicine) or products which consumers want to inspect (ex: fruit) are weaker fits for that model (1). While urgency may not be an opportunity for Instacart, if needed in under 1 hour, inspection purchases are something that the company is already trying to solve for. In his talk at the HBS Tech Conference this fall, CEO and founder Apoorva Mehta, spoke about ways they are training shoppers on how to pick the best produce and providing customer service to address and consumer concerns over product quality.

Still, businesses like Instacart will likely continue to face a contingency of consumers who are unwilling to give up their grocery shopping habits, and those who want more control over the products that end up in their cart.

[790 words]

Sources

- “The Future of Grocery: E-commerce, Digital Technology and Changing Consumer Preferences around the World.”Nielsen Global E-Commerce and The New Retail Report. Nielsen, Apr. 2015. Web. 15 Nov. 2016. <https://www.nielsen.com/content/dam/nielsenglobal/vn/docs/Reports/2015/Nielsen%20Global%20E-Commerce%20and%20The%20New%20Retail%20Report%20APRIL%202015%20(Digital).pdf>.

- Rigby, Darrell K. “The Future of Shopping.” Harvard Business Review. Harvard Business Review, Dec. 2011. Web. 15 Nov. 2016. <https://hbr.org/2011/12/the-future-of-shopping>.

- Manjoo, Farhad. “Grocery Deliveries in Sharing Economy.” The New York Times. 21 May 2014. Web. 15 Nov. 2016. <http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/22/technology/personaltech/online-grocery-start-up-takes-page-from-sharing-services.html?_r=0>.

- Web. 16 Nov. 2016. <https://www.instacart.com/>.

- S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement, 2012. Internet release date: December 2013.

Great article, Hartley! It will be fascinating to see how online grocery shopping develops in the future. I am surprised by how low the penetration rate is among millennials, I definitely thought it was higher. If this really begins to reach the mass market, it could be hugely influential on consumer goods, advertising, transport, even real estate. Ben & Jerry’s is a good example of how suppliers have already slowly begun to adapt, but I think this could really revolutionize the way CPGs reach out to customers.

I agree with you that Instacart needs to focus on the quality side of its perishable items such as fruits and vegetables as this is probably one of the biggest barriers for gaining new customers. On top of training its contracted employees, Instacart could also provide customers with a strong refund/guarantee policy to reassure them that if the products that were hand picked for them do not meet their expectations, then the mistake comes at no cost to the customer. Also, another way for instacart to grow its customer base could be to partner with stores before they roll out their own e-shopping, like stop and shop did with Peapod delivery service. It will be interesting to see how this digitization of the super market plays out over the next few years to see if people will be willing to use these kinds of services.

Great post! I’m curious whether Instacart has considered a subscription model or bulk purchasing discounts in addition to their partnerships with CPG companies. As there are many players competing in the groceries-on-demand space (e.g., Amazon, Peapod, Boxed), I wonder if Instacart will have to adjust their pricing models to provide greater value to their customers.

I’m an Instacart user and identified with a lot of the points you laid out as to why people use the service and what weaknesses it has. As other comments have mentioned, I agree that Instacart could improve it’s quality assurance policies on items that contain a lot of variability such as produce, flowers, meat, etc. Instacart also, in employing contractors, does open itself up to a lot of delivery variability. If, for example, a shopper cannot find your address or have questions about your order, they are instructed to call the customer. This can result in several phone calls with a shopper in a way that doesn’t feel more efficient than going shopping yourself. In addition to improving these pain points, I agree that the service could differentiate around bulk orders and urgent orders in order to better meet consumers different purchasing needs.

Thanks for the great post, Hartley! Thinking back to our Catalina case, I think that Instacart would be a perfect platform for integrating targeted coupons for consumers. Through your research, did you see any evidence that Instacart might move toward customized digital coupons for frequent users of the service?