M-Pesa: when “mobile money” revolutionizes banking in Africa

Did you know… that paying for a taxi ride with your mobile phone is easier in Nairobi than in Athens?

Did you know… that the continent with fastest growth in “mobile money” is Africa, a continent (too) often regarded as lagging behind the rest of the world?

Of the top twenty countries for mobile money usage, fifteen are indeed in Africa[1]. In 2012, the continent’s mobile market was worth more than $50 billion, i.e. more than the total money sent via mobile in both Europe and North America[2]. M-Pesa, Kenya’s world-leading mobile-money system, played a massive role in this success.

Strong lack of financial inclusion in Africa

Less than 35% of the adult population in Sub-Saharan Africa has access to financial services[3]. Such a lack of financial inclusion is mostly due to the fact that banks consider the financial case for inclusion to be negative. However, a majority of analysts say that “over the coming years, mobile money, electronic payments and new banking technologies will continue their significant contribution to sustainable economic development”[4] in Africa. Only a limited number of initiatives have reached a sustainable scale to date: M-Pesa in Kenya (Exhibit 1), MTN Uganda, Vodacom Tanzania or FNB in South Africa[5].

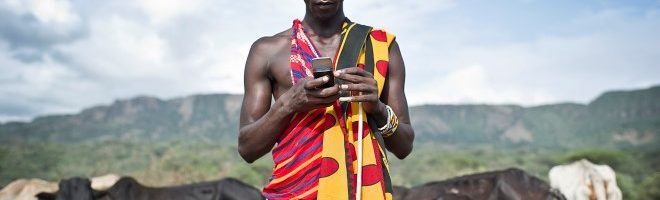

Exhibit 1

M-Pesa, a “best-in-class” example

In 2007, Safaricom (Kenya’s largest mobile network operator) launched “M-Pesa”: “M” is for mobile, “Pesa” is for money (Swahili). The concept was simple: any “M-PESA customer” can use his or her mobile phone to “move money quickly, securely, and across great distances, directly to another mobile phone user”[6].

How M-Pesa used digital at the beginning…

Digital innovations helped the company develop an innovative and compelling value proposition. Indeed, M-Pesa was:

Easy – The customer does not need to have any bank account, any fancy smartphone or any high-speed internet connection. He or she only needs to register for an M-Pesa account with Safaricom. It is also very easy for a customer to find an agent/”Safaricom dealer” – more than 50,000 of them being spread across the country (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2

Intuitive – Customers transform cash into e-money at “Safaricom dealers” and follow simple instructions on their phones to make payments.

Secure – The account is secure, PIN-protected and supported with a full time customer service.

… and later on…

However simple the concept might seem, technology was a key driver in how significantly the value proposition evolved after the initial launch.

First, the intent was to create a service which “would allow microfinance borrowers to conveniently receive and repay loans using the network of Safaricom airtime resellers”[7]. Very quickly, customers started to send remittances home and M-Pesa evolved to a “general money-transfer scheme”[8]. More recently, M-Pesa was extended to offer loans and savings products, or even to disburse salaries or pay bills.

… to meet a growing and sustainable success

Within its first month of operations, Safaricom registered over 20,000 customers – way more than the targeted business plan[9]. Today, M-Pesa is used by over 25 million active customers[10], after recent expansion to new countries such as Afghanistan, South Africa and Romania. For Kenya only, around 25% of the country’s gross national product flows through it.

The business model also seems to be sustainable for Safaricom: on the topline, users are charged a small fee for sending or withdrawing money. On the bottom line, M-Pesa built on their existing mobile credit sellers, turning them into “mobile money agents” with very limited investment and additional costs.

The impact on community was also impressive: in rural Kenyan households which adopted M-PESA, average income increased by 5-30%[11]. In addition, the availability of a reliable mobile-payments platform led to a huge increase in the number of start-ups in Nairobi.

Potential for improvement

Critics point out that the advanced technology was not the reason why M-Pesa was so successful. Some experts said that M-Pesa was “built mostly on a favorable regulatory and technological environment absent in other markets. […] For things to work, you need a country with supportive regulation and reversals in cultural attitudes that often view money as meaning cash“[12]. In addition, in other countries with less favorable regulation dynamics, M-Pesa was far less successful.

Moreover, the barrier-to-entry to this market is very low. Today, many banks are designing services with lower technological requirements and easier offerings. For instance, in 2012, Barclays introduced “Ping-it” (Exhibit 3), a payment method that allows one to send or receive up to £300 a day to or from other people, just by using a mobile phone number. Its success was impressive, with more than one million downloads in the first six months.

Exhibit 3

In front of such challenges, will M-Pesa manage to leverage its first mover advantage and achieve enough technological improvement to become a sustainable leader?

(796 words)

[1] Rachel Bostman, “Mobile money: the African lesson we can learn”, quoting a survey conducted by the Gates Foundation, the World Bank and Gallup World Poll

[2] Rachel Bostman, “Mobile money: the African lesson we can learn”

[3] http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2015/04/15/massive-drop-in-number-of-unbanked-says-new-report

[4] “Mobile banking hailed as a key driver for financial inclusion in Africa”, Africanews: http://www.africanews.com/2016/09/21/mobile-banking-hailed-as-a-key-driver-for-financial-inclusion-in-africa/

[5] Beth Cobert, Brigit Helms, and Doug Parker, “Mobile money: Getting to scale in emerging markets”, McKinsey & Company

[6] Nick Hughes and Susie Lonie, “M-PESA: Mobile Money for the “Unbanked”. Turning Cellphones into 24-Hour Tellers in Kenya”

[7]“Assessing Regional Integration in Africa IV”, Economic Commission for Africa, African Union, ADB, 2010

[8] http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2013/05/economist-explains-18

[9] Nick Hughes and Susie Lonie, “M-PESA: Mobile Money for the “Unbanked”. Turning Cellphones into 24-Hour Tellers in Kenya”

[10] https://www.vodafone.com/content/index/media/vodafone-group-releases/2016/mpesa-25million.html

[11] http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2013/05/economist-explains-18

[12] “Africa Leading the Way in Adoption of Mobile Banking”, Agence France-Presse, 28 April 2015

It is fascinating that mobile commerce is so much more common in Africa than elsewhere! It seems like M-Pesa is very much like venmo in the US and it can almost function as a standalone bank account. It does seem like it is subject to network effects such as what we saw with Uber during class last week – in order to be successful, it must be widely used throughout the country. I think that given that they’ve achieved scale with their network in Nairobi they were right to move into adjacent products such as loans that are more “sticky.” This will likely help them sustain their success longer term.

M-Pesa is a fascinating case. It is a company owned by the cellphone provider network and works on SMS technology. This technology although old is applicable to Africa since the country does not have high smart phone penetration.

I believe the most interesting thing of MPesa is the way it has facilitated the financial inclusion and financial transactions in an under developed country. It is fascinating how each store can accept money into the MPesa account. Also MPesa helps the community by creating a the ability of microfinancing.

How do we make the MPesa model work in other under developed economies? This technology is ripe for many countries with low smart phone penetration.

Great post. Africa has truly emerged as a hotbed of mobile innovation, and a lot of companies (like Safaricomm) are finding that countries like Kenya are perfect candidates for beta and concept testing. Tala (formerly Inventure), for example, is a fintech company that aggregates thousands of unconventional data points to generate credit scores for low-income individuals and the unbanked in third world countries. When their operations in India (their initial target market) began to lose steam, they set their sights on Kenya. As you noted in your article, they found a happy blend of regulatory cooperation, cultural norms that did not necessarily equate money with cash, and a market that was eager to adopt unproven technology.

The availability of mobile technology is not enough to generate meaningful momentum — it’s willingness on behalf of potential consumers to trust technology and a firm commitment on behalf of governments to allow for digital exploration.

Interesting post! M-Pesa’s business is extremely fascinating. The impact they had on rural Kenyan households is amazing and quite inspirational for many tech companies to start/expand businesses in underdeveloped areas. Although I do agree with the statement that M-Pesa was successful not only because of technology but also because of the country’s regulatory environment, I think it will also be critical for M-Pesa to create products and services that will differentiate itself in such an environment to continue to be sustainable.

Hi Maya, I am always excited when people highlight the opportunities opened up by branchless banking. How did you arrive at the $50bn valuation number for the 2012 mobile money market? In context that is the same as Kenyan GDP in the same year. The largest provider, M-Pesa represents around 10% of Safaricom Net income, and MTN, a far larger teleco than Safaricom, has a total market cap of $20bn across all of its African, Asian and Mid-East markets.

Others estimate that the mobile money market in Africa will be worth $14bn by 2020, from circa $2bn as of 2015: http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20150921005630/en/Research-Markets-Africa-Mobile-Money-Market-2015. I like this articlehttp://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/SOTIR_2015.pdf.

How would you counter their valuation arguments?

Great post on the power of applying even basic technology in new ways or in new environments. One question:

Growing and achieving scale is central to M-Pesa’s model. However, the first concern I had was that their size makes them an attractive target to hackers. I did some research and discovered that two years ago, Kenyan officials discovered and arrested a cybercrime ring operating out of Nairobi “equipment capable of a massive cyber attack, such as infiltrating Safaricom’s M-Pesa (mobile money transfer) system, cash machines and bank accounts” [1]. Although this ring had not attacked M-Pesa, it seems like it is only a matter of time before either hackers attack or the Kenyan government introduces stricter regulation around digital cash transfers.

You asked at the end of your post if M-Pesa could “leverage its first mover advantage and achieve enough technological improvement to become a sustainable leader.” I posit that one key way M-Pesa could do this would be to invest in cybersecurity measures and cooperate with the Kenyan government proactively to ensure it is seen as a regional (and perhaps global) leader in this space. This could enable M-Pesa to expand into other markets that were previously closed to them and avoid the risk of a crippling, potentially fatal cyberattack.

[1] http://pcmlp.socleg.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2015/06/Gagliardone_Sambuli_CyberSecurity-2.pdf

What an interesting post! Amazing how a cellular company became one of the biggest financial players in Kenya. My question is – how transferable is this success to other countries? As you mentioned, M-Pesa was less successful in other countries due to regulatory conditions. I suspect there’s more to it than that. I think two crucial factors enabled M-Pesa’s success: 1. The existing distribution network of Safaricom dealers. 2. Traditional retail banking penetration level in Kenya was low. I’m not sure how many other countries can exhibit these two condition. As far as the second factor: if we look at data from the World Bank using percentage of male adults with an account at a financial institution as an indicator for financial services penetration (see: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/WP_time_01.2?view=map ) – countries without high level of financial service penetration are scarce and located mostly in Africa.

Thanks for a great post.It is astounding to think about the breadth of impacts that mobile money can have on sub-Saharan African countries, where financial inclusion has historically been so low. The impacts of mobile money extend far beyond the private sector: governments and non-profit organizations are increasingly relying on the vast number of mobile money users to carry out their programs. For example, in Kenya, M-Pesa has been used to deliver cash transfer programs to poor households; this has dramatically increased the efficiency of these programs, as the physical distribution and collection of cash was time-consuming for both the provider and the recipient, and the transaction opened the door for money to be taken along the way. With mobile money, the transfer is instant, regular and there is a clear record of the amount sent and received.