Jaguar Land Rover: A Bumpy Ride post-Brexit

Is Jaguar Land Rover, the UK’s largest auto manufacturer, heading for a car crash? Jaguar’s integrated supply chain is set to face massive disruption as uncertainty reigns over Britain’s relationship with the EU.

A Bumpy Ride: Brexit and the UK Auto Industry

The UK’s historic Brexit vote on 23 June 2016 sent the domestic car industry reeling. Not only are 53% of cars produced in Britain sold in the EU [1], but on average 60% of the components of those cars are imported from the continent [2]. With such heavily integrated supply chains, is the industry headed for a car crash?

Brexit threatens the comfortable zero-tariff, zero customs controls relationship between Britain and Europe which thus far has helped British automakers thrive. Firstly, it’s as yet uncertain whether the UK and the European Union (EU) will agree on a new free trade agreement. Even if they do, strict “rules of origin” regulations will likely require UK-produced vehicles to meet a threshold percentage of domestically-sourced component parts, to be eligible for tariff-free trade [3]. Failing to meet that threshold raises the spectre of World Trade Organisation tariffs – up to 10% on vehicles and 4.5% on component parts – plus the introduction of customs controls [4].

Jaguar Land Rover: Hitting the Brakes?

As the UK’s biggest automotive company, Jaguar Land Rover (JLR) is greatly exposed to these risks. An internal memo written pre-Referendum estimated that Brexit could hit profits by over £1bn by 2020 [5]. Much of that is due to the havoc such trade barriers might wreak on JLR’s supply chain. Although JLR exports only 20% of its cars to the EU [6], the company imports 40% of its materials from the continent [7].

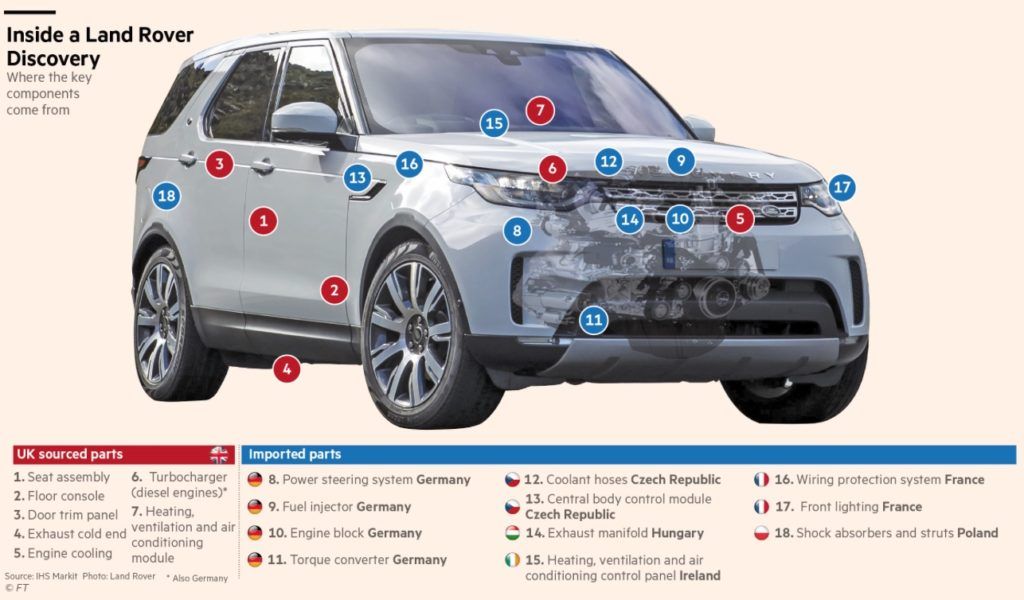

Figure 1: 18 of the 25 parts in Jaguar Land Rover’s Land Rover Discovery come from Europe [8]

Tariffs are only half of the story. With the UK out of the European customs union, new customs controls may hit the brakes on daily deliveries of millions of components to JLR’s UK factories – disrupting and delaying JLR’s finely-tuned ‘just-in-time’ production process [9]. While JLR could hold buffers to allow time for customs inspections, they would face increased inventory costs and further hurt profitability.

The solution isn’t as obvious as simply sourcing more components locally. According to CEO Ralf Speth, “we source a high degree of components in continental Europe, and at the very moment the technology is not in the UK – so there is not another choice” [10]. That said, JLR has already started to take action to address this concern.

In the Driving Seat

JLR’s first action has been ‘reshoring’: bringing offshore operations back to home ground. JLR and its peers have been putting pressure on British industry to increase its component manufacturing capabilities. It seems to be working: in 2017, 44% of the parts used to build British cars were sourced domestically, up from 41% in 2015 [11]. Other successes include convincing a French bumper supplier to move its production to the UK in time for the recent launch of a new Range Rover model [12].

On the other hand, if JLR cannot source enough of its component parts domestically, its alternative is to move car production to Europe. As part of a pre-Brexit strategy to expand its international footprint, JLR has been doing just that: production will soon begin at new sites in Slovakia and Austria. JLR senior management have described the new facility in Slovakia as “a hedge by default” against a deterioration in British trading conditions [13].

The Road Ahead

While it would not be prudent for JLR to undertake major strategic shifts without further certainty regarding Brexit negotiations, there is some further action its management could take.

Currently, JLR plans to produce just one model in each of the Austrian and Slovakian plants, while 12 models are manufactured across the three UK sites [14]. The company may consider diversifying its production by reallocating further models to these new European facilities.

JLR can also use its clout, as the UK’s flagship auto producer, to tap in to the political sphere. To aid its reshoring efforts, the company could work with lobby groups to advocate for funding grants to help relocate component suppliers to the UK. In such discussions, the threat of shifting production outside Britain could be a powerful bargaining tool for JLR and its peers.

Driving Away

Some open questions remain. I’m particularly concerned about JLR’s (and the broader industry’s potential reliance on a successful reshoring campaign. It is a tough sell. Realistically, how much opportunity is there for parts-makers to produce in the UK, compared with the much larger auto markets of France and Germany? If this is deemed to be limited, what is their incentive to invest in expensive new facilities in the UK?

Secondly, Brexit won’t just impact the UK-EU supply chain. 56% of JLR’s sales are to the rest of the world [15]. Post-Brexit, as the UK renegotiates terms with all its trading partners, what further ramifications will this have for JLR?

Word Count: 800.

References

[1] Ford, Jonathan. “Profiting From Brexit: McLaren shifts supply chain back to the UK.” The Financial Times, 9 September, 2017. https://www.ft.com/content/b3d67800-9475-11e7-bdfa-eda243196c2c, accessed November 2017.

[2] The Economist. “Britain’s car industry gets a Mini boost but faces major problems.” 27 July, 2017. https://www-economist-com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/news/britain/21725584-bmw-announces-welcome-investment-road-ahead-looks-bumpy-britains-car-industry-gets, accessed November 2017.

[3] Seal, Thomas and Ward, Jill. “Cars Made in U.K. May Struggle to Be British Enough Post-Brexit.” Bloomberg , 21 August, 2017. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-08-21/cars-made-in-u-k-may-struggle-to-be-british-enough-post-brexit, accessed November 2017

[4] The Economist. “Britain’s car industry gets a Mini boost but faces major problems.” 27 July, 2017. https://www-economist-com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/news/britain/21725584-bmw-announces-welcome-investment-road-ahead-looks-bumpy-britains-car-industry-gets, accessed November 2017.

[5] The Guardian. “Brexit could cause £1bn drop in Jaguar Land Rover profit by 2020.” 21 June, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/jun/21/brexit-could-cause-1bn-drop-jaguar-land-rover-profit-sources-say, accessed November 2017.

[6] The Economist. “Britain’s car industry gets a Mini boost but faces major problems.” 27 July, 2017. https://www-economist-com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/news/britain/21725584-bmw-announces-welcome-investment-road-ahead-looks-bumpy-britains-car-industry-gets, accessed November 2017.

[7] Campbell, Peter and Pooler, Michael. “Brexit triggers a great car parts race for UK auto industry.” The Financial Times, 30 July, 2017. https://www.ft.com/content/b56d0936-6ae0-11e7-bfeb-33fe0c5b7eaa, accessed November 2017.

[8] ibid.

[9] Seal, Thomas and Ward, Jill. “Cars Made in U.K. May Struggle to Be British Enough Post-Brexit.” Bloomberg , 21 August, 2017. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-08-21/cars-made-in-u-k-may-struggle-to-be-british-enough-post-brexit, accessed November 2017

[10] Speth, Ralph. “Jaguar CEO Says Future of Automobile Industry is Electric.” Interview on Bloomberg Daybreak: Europe, 7 September, 2017. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/videos/2017-09-07/jlr-ceo-future-of-automobile-industry-is-electric-video

[11] The Economist. “Brexit triggers a round of reshoring.” 19 October, 2017. https://www-economist-com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/news/britain/21730479-firms-shorten-their-supply-chains-divorce-europe-nears-brexit-triggers-round, accessed November 2017.

[12] Campbell, Peter and Pooler, Michael. “Brexit triggers a great car parts race for UK auto industry.” The Financial Times, 30 July, 2017. https://www.ft.com/content/b56d0936-6ae0-11e7-bfeb-33fe0c5b7eaa, accessed November 2017.

[13] Islam, Faisal. “Government faces Brexit revolt from unhappy carmakers over customs.” Sky News, 18 September, 2017. https://news.sky.com/story/government-faces-brexit-revolt-from-unhappy-car-makers-over-customs-11041724, accessed November 2017.

[14] Jaguar Land Rover. 2017 Annual Report. http://annualreport2017.jaguarlandrover.com/assets/files/jlr_ar16_17.pdf, accessed November 2017.

[15] ibid.

Very interesting and well-written! I didn’t realize that Jaguar Land Rover produced so much of its cars in the UK and imported so many of its parts from the rest of the EU. They certainly seem to be more exposed to the effects of Brexit than most. I’m not optimistic that a new free trade agreement will be very favorable toward Britain. I agree that JLR’s best move at this point is to diversify production allocation across its plants. With so much uncertainty surrounding Brexit negotiations at this point, it’s definitely a challenge to stay ahead of the game. I’m not normally a fan of passiveness, but maybe a “wait and see” approach will be best in this situation.

Thanks for sharing!

Given that the automobile industry’s parts-makers are so fragmented, it is difficult to generalise what their reactions to any demand by JLR will be. But for those with whom JLR holds a large share of wallet, and who cannot realistically relocate their production to the UK, JLR could have significant negotiating power and share with them some of the tariffs cost increase.

On another note, further depreciation of the GBP as the Brexit negotiations unfold could actually provide positive tailwinds for UK exports to the rest of the world!

Insightful write-up Erik!

While I agree that shifting additional model production to non-UK plants in continental Europe (like Austria and Slovakia) may be a viable option to hedge against Brexit uncertainties, I am curious as to what you think about potential negative consumer reaction and demand to a Land Rover / Jaguar that is not produced in Britain on paper. As I understand, the British heritage and finesse behind these iconic luxury brands remains a large draw for consumers, particularly those located in growing emerging markets like China. When India’s Tata Motors acquired Land Rover & Jaguar, many were already concerned about the sustainability of the brands’ “British authenticity” moving forward. We also saw similar black-lash when China’s Geely acquired the iconic Scandinavian Volvo marque. While these rumblings in the media may be short-lived, I wonder if they hold a longer, more permanent effect on how consumers perceive and engage with these luxury brands – enough to make JLR second think their outsource production strategy.

While Brexit has come as a shock to many, Switzerland and Norway have shown that there is no reason to be overly pessimistic. Both countries are not members of the European Union (EU), but still many of their companies have successfully weathered some of the tough dynamics that will impact JLR going forward: instability of political boundary conditions, intricate trade agreements in a constant state of flux, and highly volatile exchange rates. During the days after Brexit, officials from the UK met with politicians from Switzerland to seek inspirations for potential political agreements with the EU. In a similar vein, JLR should draw lessons from Swiss and Norwegian companies.

I have seen Swiss companies taking action along three dimensions to become more resilient. All of them touch the supply chain in various aspects and could open up new opportunities for JLR:

* Operations: Investments in automation and offshoring of services that are not subject to tariffs or trade restrictions (e.g., internal white-collar staff functions) have taken a toll on short-term profits, but helped many companies to become more profitable in the long run. For JLR, these actions could mitigate some of the costs related to “reshoring” operations mentioned in the essay.

* Political activism: In Switzerland, difficult trade negotiations with the EU and tough macroeconomic conditions have increased the level of cooperation between private sector actors, government agencies, policy makers, and unions. These “roundtables” went beyond the reshoring-focused lobbying efforts mentioned in the essay; they have improved the overall business environment by reducing taxes, cutting red tape, adjusting labor laws, and paving the road to trade agreements with emerging markets that offer new export opportunities beyond traditional markets.

* Strategic re-evaluation: A relentless focus on the most profitable parts of the value chain has allowed companies to find the optimal degree of vertical integration. Rediscovering their “true edge” has enabled them to maintain – and in many cases, even to strengthen – their competitive advantage.

At first glance, Brexit poses many new hurdles for JLR. Lessons from corporations in Switzerland and Norway, however, provide ample reasons to be confident and optimistic about the British future of JLR.

In theory, re-shoring sounds like the most effective way to combat new restrictions on supply sourcing. However, an increase from 41% to 44% of parts sourced domestically over a two-year time frame does not seem significant – additional investment is warranted. If JLR wants to weather the Brexit storm, they need to weigh paying tariffs for using established auto markets versus increasing their domestic capabilities via new facilities/plants for the long-term. It is important to consider how they want to be positioned for other world-wide trends (think: Trump and potential trade implications), above and beyond Brexit.

In addition to higher tariffs and diminishing value of the pound, something else to consider is inventory control [1]. Can JLR be proactive in their production approach by securing long-term contracts with suppliers or “stealing” domestic producers from competition, thereby locking in the market? Potentially they can also have a better understanding of future forecasts, such that they can pre-produce inventory before these effects fully take place.

[1] “How Companies Should Prepare for Brexit”, Bain & Company, April 2017, http://www.bain.com/publications/articles/how-companies-should-prepare-for-brexit-wsj.aspx

A great choice for a topic, great write-up as well! While I’m not nearly as familiar with Brexit as I should be, your questions at the end really interest me. To me, JLR seems like a large enough company to warrant major parts manufacturers re-shoring their operations within the UK.

Some may refuse, but the overall demand is there that someone will be incentivized to step into that void to produce the parts JLR needs. I think of this as more of a short term issue than anything. Hopefully the supply chain will correct for itself in the long term, either in the form of a new free trade agreement being passed between the EU and UK or the eventual building of long term factories on British shores needed to supply JLR at cost effective prices.

I personally think the larger issue is between the UK and the rest of the world. As you point out, JLR sells 56% of its cars to the rest of the world. Will the UK companies maintain the same bargaining power at the trade table that they once had while they were in the EU? If they get a much worse deal than they once had, will JLR be forced to exit some countries? These questions are out of my pay grade, but it makes me also think about the opposite scenario, what if the UK is able to negotiate far superior trade deals since they were one of the stronger countries in the EU? Would JLR flourish under this scenario? Or are the differences in trade agreements so negligible there won’t be that much of a bottom line effect either way.

Very well written.

While 40% of the imports might be sourced from the EU, I wonder if the currency advantage will be a key driver in JLR staying in the UK. If 54% of their sales is to the rest of the world, they were just handed a 10% bump in profits in June 2016 thanks to Brexit. It is an interesting trade-off that I suspect banks are grappling with as well – staying headquartered in the UK undeniably gives them a cost advantage in the short to medium term (as long as the uncertainties around the negotiations cast a pall on the GBP) but in the long-term supply chain disruptions will force adjustments. Interesting time to be a CEO of a UK company.

Ultimately, re-shoring alone doesn’t need to be the answer – they could do something similar to unilever (which is to match their manufacturing and sales locations as closely as possible). In other words, this would mean a shift to a distributed model of production rather than a centralized one. Necessity is the mother of all innovation and we might be in for a pleasant surprise.

This ‘reshoring’ is exactly what the proponents of protectionism want to happen. By making it more expensive to bring goods from abroad, protectionism seeks to foster local production. Being a free-market advocate myself, it upsets me that it is working! As you mention, British car-makers are sourcing more parts from within the UK. This is common across all OEMs in Britain and in fact there is a Guardian article mentioning a potential Government investment of 100 to 140 million pounds to ‘repower the supply base’. This is concerning to me since eventually manufacturing plants in the UK will only chose their sourcing from a limited subset of the world’s market of component supplier (only those in the UK) which may not be as competitive. Additionally, the entire English auto-making industry may loose global competitiveness, from both increased production costs and retaliatory tariffs by trade partners, and stall altogether. Sure, they’ll be producing cars with a majority of British parts, but probably much fewer of these.

Very nicely written!

Article: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2017/feb/28/brexit-taxpayers-support-supply-chain-nissan-sunderland-car-auto

Very well written – thank you for your thoughts. This may be stating the obvious but after reading this my questions is why are they not exploring sourcing more of their components from outside of continental Europe (i.e. emerging markets)? Are there supply or geographical / delivery / cost constraints due to which they are not doing so?

Great article! This is a very interesting topic, and an issue that UK vehicle manufacturers continue to grapple with.

The fact that it is taking so long for the UK and the EU to come to an agreement on the terms of the UK’s separation from the union is causing a lot of anxiety. After five years of continuous growth, new car sales have begun to fall due to uncertainties over how Brexit will affect the UK automotive industry [1]. The UK government is trying to help by supporting manufacturers of vehicle assembly components. For example, the government sponsored a 246 million pound competition to support the battery supply industry [2],, but I am not sure how much of an effect it will have.

JLR, as well as the other UK car manufacturers have a long and difficult road ahead of them as they work to understand the full extent of Brexit’s impact on their businesses, as well as if they can remain competitive globally.

[1]”Brexit uncertainty blamed as uk car sales fall for fourth month” The Guardian Newspaper https://www.theguardian.com/business/2017/aug/04/brexit-uncertainty-blamed-as-uk-car-sales-fall-for-fourth-month – Accessed December 2017

[2] “Profiting from Brexit: McLaren shifts supply chain back to the UK” The Financial Times https://www.ft.com/content/28787548-8c82-11e6-8cb7-e7ada1d123b1 – Accessed December 2017

What an interesting article on JLR’s post-Brexit quandary. I certainly agree with you that reshoring will be a difficult process with uncertain outcomes.

Have you considered, however, the potential positive effect of the depreciation of the pound sterling following the announcement of Brexit? European carmakers importing to the UK will find that the falling pound reduces their earnings. JLR enjoys the opposite effect, with earnings from the EU enjoying a boost due to the strength of the euro. This at least provides JLR with a financial cushion while it carries out its reshoring operations.

I agree that relying too much on a successful reshoring campaign is a tough sell. Particularly with how much of their sales are Europe and ROW. If I were sitting in the Jaguar Land Rover board room I would be advocating to invest more in the ‘hedge’ strategy by preparing to add capacity outside of the UK. I hear the concern on it deteriorating the brand, but I wonder if it could follow a model similar to how Mercedes handles their luxury AMG line in the US. The AMG lines are marketed toward the heavily discerning consumers with high willingness to pay and the fact that they are manufactured by craftsman in historic factories in Germany is part of the brand. However, the bulk of cars sold by Mercedes Benz USA in the US market are manufactured in the US (they are expanding this capacity and just invested a billion in a new plant in Alabama). My hope would be that by expanding capacity outside UK with Slovakia and potential new locations you can scale up to meet to meet the demand of cost conscious customers who prioritize cost over the heritage of manufacturing location, and at the same time keep your high end vehicles manufactured in the UK where increased costs due to tariffs can be absorbed in the price as it is marketed to the more discerning customer with a desire to pay for the UK heritage.

https://www.voanews.com/a/mercedes-benz-invest-billion-in-us-electric-car-plant/4039726.html