Do More with Less: Can Machine Learning Help Feed the Growing Population?

How do we feed a growing population in the face of a changing climate and diminishing natural resources, all while protecting our planet? Monsanto thinks it has the answer: machine learning.

Do more with less.

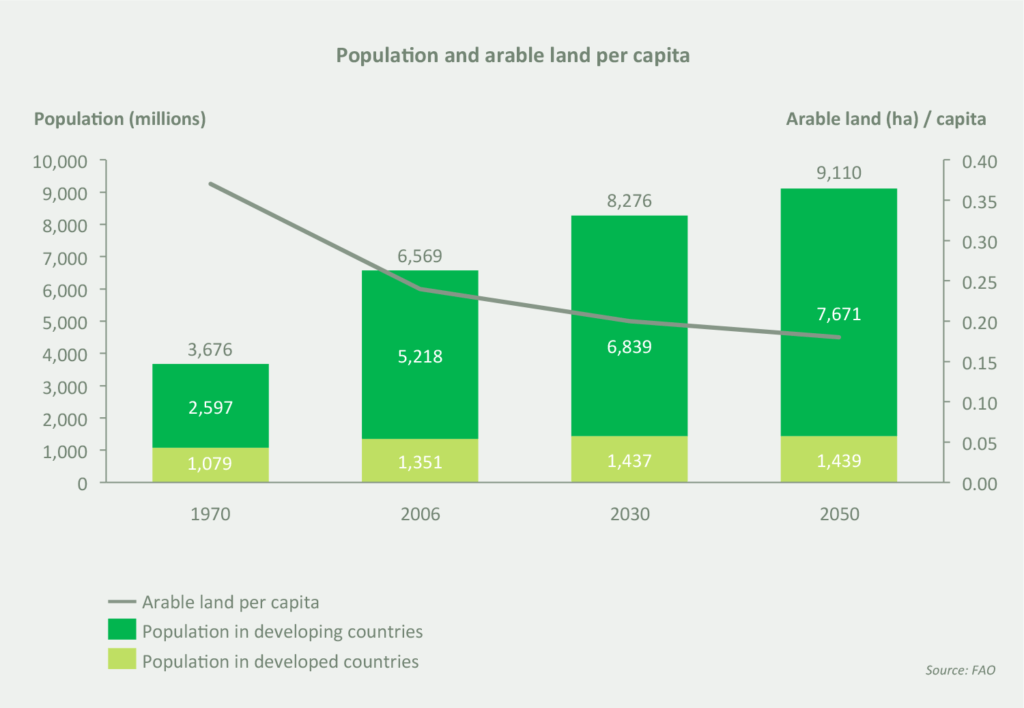

Anyone in business is familiar with this mandate, but for the agriculture industry trying to live up it, the stakes could not be higher. By 2050, the global population is expected to reach 9.7 billion people. To support this growth, food production must increase by 50-90%.[1]

Meanwhile, climate change is bringing extreme weather and depleting natural resources. Urbanization is diminishing the amount of arable land. Crop yields have plateaued.[2] How do we cope with the rising demand for food production in the face of diminishing resources, all while protecting our planet?

Monsanto

One answer is through increasing crop yields. Agriculture giant Monsanto tackled this problem in the past by developing herbicides and pesticides (most infamously, RoundUp) and genetically modified seeds that boosted crop resistance to weather and disease. However, the severe health effects of these chemicals, coupled with other controversial practices, led to consumer protests in the early 2000s. As farmers rejected Monsanto in favor of healthier alternatives, shares plummeted.

A new chapter

Meanwhile, start-ups began applying big data to solve these problems. Using satellites and sensors, these start-ups developed tools to observe and measure crop variability. Recognizing the competitive pressure and changing farmer demands, Monsanto refocused on a new strategy: machine learning.

In the short-term, Monsanto leveraged machine learning to improve its internal supply chain and product development processes. It adopted a new Transportation Management System where algorithms now monitor and optimize transportation routes in real-time. In Brazil alone, this helped reduce total vehicle miles by 1.4 million in the first year.[4]

Further, Monsanto adopted machine learning to speed up its R&D timeline. Rather than test seeds manually, researchers now use algorithms to analyze past performance of various strains in similar conditions and predict future resilience, saving hundreds of hours of research time.[3]

Yet the biggest transformation Monsanto has undertaken is a long-term bet: transitioning from a seed and pesticide company to a technology company.

Every year farmers wrestle with countless questions about how to optimize crop yields — which seeds to plant when, how much to irrigate, when to harvest — and analyze and predict the effects of a wide range of externalities — weather, disease, changing consumer preferences. In 2013, Monsanto made a $1 billion long-term bet that machine learning could help answer these questions when it acquired The Climate Corporation.

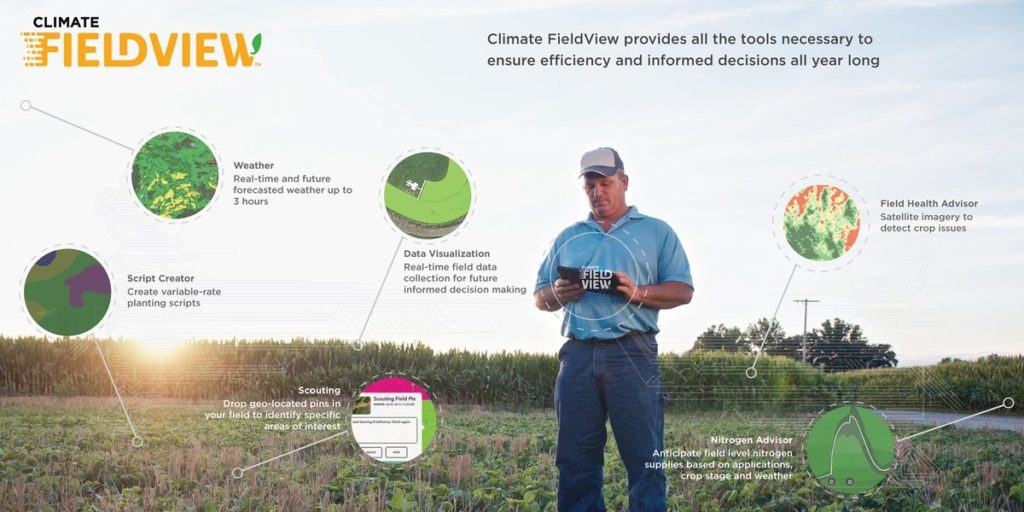

Together with Climate Corporation, Monsanto launched Climate FieldView, an application that uses machine learning to create bespoke seed “prescriptions” according to a farmer’s specific soil conditions and weather predictions. A farmer inputs their field data into Climate FieldView, and the platform will instantly combine that data with historical trends from similar soil, weather, and crop patterns and deliver tailored crop management insights — from how much water to use, to the amount of nitrogen to add to soil, to the optimal time to harvest.[5] Studies in 2014 showed that using these technologies reduced cost inputs by 15% and increased crop yield by 13%.[8]

Looking forward

Going forward, Monsanto could use machine learning to further improve crop yields. The A.I. used to power autonomous vehicles is easily transferable to agriculture; imagine an autonomous tractor that could drive the field, analyze in real-time whether a crop is ready for harvest, and either harvest or leave to let ripen. This would further reduce costs and eliminate waste.

However, for these algorithms to be successful, Monsanto needs access to training data — data on crop outcomes from thousands of farms around the world. Yet, the individual farmer may not want to give up that data, as this historical knowledge was once a competitive advantage. After all, if all farmers use Climate FieldView, will small farms be able to compete? Further, when farmers use Climate FieldView, who owns the data on crop outcomes? Can Monsanto share the data with, say, crop insurance providers?

Success hinges on farmers trusting Monsanto to use their data for good. Given Monsanto’s history of unethical practices and monopolistic abuse, that trust may be difficult to win. Thus, Monsanto needs to focus on rebuilding trust within the farmer community.

Open questions

We have seen how machine learning has helped Monsanto and its customers become more efficient with food production. This is crucial if we are to feed a growing population sustainably and preserve the earth’s natural resources.

Yet open questions remain. Just as individuals now grapple with companies like Facebook and Google regarding data ownership and monopolistic power, the agricultural world faces the same questions with Monsanto. For a company who has long abused its seeming monopoly over seeds, does this aggregation of data give them too much power? What are the risks in Monsanto owning all data on crop outcomes? We know using machine learning can help improve crop yields, but what is the price?

[Word Count: 798]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. “Feeding the World, Eradicating Hunger.” via http://www.fao.org/tempref/docrep/fao/Meeting/018/k6077e.pdf

- Foley, Jonathan A., Deepak K. Ray, Nathaniel D. Mueller, and Paul C. West. “Yield Trends are Insufficient to Double Global Crop Production by 2050.” 19 June 2013. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0066428

- Swanson, Jim and Naveen Singla. “Inside Monstanto’s Digital Transformation.” DataScience.com. 16 July 2018. https://www.datascience.com/blog/inside-monsantos-digital-transformation. Accessed November 2018

- “Data Analytics in the Global Supply Chain.” Monsanto. 16 January 2018. https://monsanto.com/company/articles/data-analytics-global-supply-chain/ Accessed November 2018

- “Digital Agriculture’s Leading Farm Software Platform.” Climate Fieldview, www.climate.com/.

- “Monsanto to Acquire The Climate Corporation, Combination to Provide Farmers with Broad Suite of Tools Offering Greater On-Farm Insights.” Monsanto, monsanto.com/news-releases/monsanto-to-acquire-the-climate-corporation-combination-to-provide-farmers-with-broad-suite-of-tools-offering-greater-on-farm-insights/.

- Charles, Dan. “Should Farmers Give John Deere And Monsanto Their Data?” NPR, NPR, 22 Jan. 2014, www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2014/01/21/264577744/should-farmers-give-john-deere-and-monsanto-their-data.

- Byrnes, Nanette. “Silicon Valley Takes a Trip to the Farm Belt.” MIT Technology Review, MIT Technology Review, 16 Sept. 2016, www.technologyreview.com/s/537596/internet-of-farm-things/.

At the end of your analysis, you posted a few questions. You asked that for a company who has long abused its seeming monopoly over seeds, does this aggregation of data give them too much power? What are the risks in Monsanto owning all data on crop outcomes? We know using machine learning can help improve crop yields, but what is the price? I am a strong believer in needing advanced technology to feed the future population. Machine learning is one way to increase crop yield. And with machine learning comes management and control of data. While it is entirely possible that one company that holds the aggregation of data will come to have more power than its peers, I do believe in the power of market competition. If this technology proves to be lucrative, other firms within the space will likely enter to drive down the price of the offering and enhance technological edge to take a slice of the pie. At the end of the day, the problem that needs to solved is feeding the world’s population by increasing yield crop and whoever can do it first will get to set the price but eventually a price equilibrium should be reached where the market is sustainable for the population to purchase (otherwise government will have to intervene).

Really interesting essay that helps me better understand the cross-section of machine learning, big data and agriculture. One thing that would be helpful to understand is where the data feeding this software comes from and how reliable it is. Is this data open source or is this data proprietary to Monsanto? Are there risks or biases in the data that could companies or people could use in dangerous ways? Furthermore, i would be curious to learn about the iterative nature of the system. Right now it seems like a single output comes from a series of inputs but how is Monsanto bringing new data into the system and constantly iterating on it?

Great question. The data comes from a few sources — for things like weather predictions it comes from public databases like weather.gov. Some data is crowd-sourced, so it comes from other farmers’ data that has either been uploaded manually by users of Climate FieldView or uploaded automatically via sensors, drones, and other technology the farmer might be using. Everything runs off of the cloud so it’s all iterative and learns as it ingests or receives more data. So, to your point it is iterative and there are network effects. For example if a farmer uploads a picture of a crop because he’s wondering what disease it has, that is compared to pictures of the same crops that other farmers have uploaded.

Although I personally have no problem with GMOs and don’t know any farmers who do either, I definitely know many who are not well pleased with Monsanto’s previous practices, so I think the trust issue is definitely the key point. It seems like all future companies will be in the data business. The ones with the most data will win and, to a certain extent, that’s good. It incentivizes companies and individuals to be on the cutting edge. Then the market rewards them. Unfortunately, to Al’s point, the monopolist seldom neglects to erect barriers to entry and success begets more success. If you look at tech today, while there are many many companies, most don’t have a direct competitor: Google is dominant in search, Microsoft in OSs, Facebook in social networking, etc. Because of this, I do share the author’s concerns about a furthering of Monsanto’s hegemony in the global agriculture industry.