Crowdsourcing a Pharma Breakthrough: Lilly’s Open Innovation Drug Discovery Program

Given increasingly costly (and decreasingly effective) Research and Development in the pharmaceutical industry, can Lilly crowdsource innovation using its Open Innovation Drug Discovery (OIDD) Program?

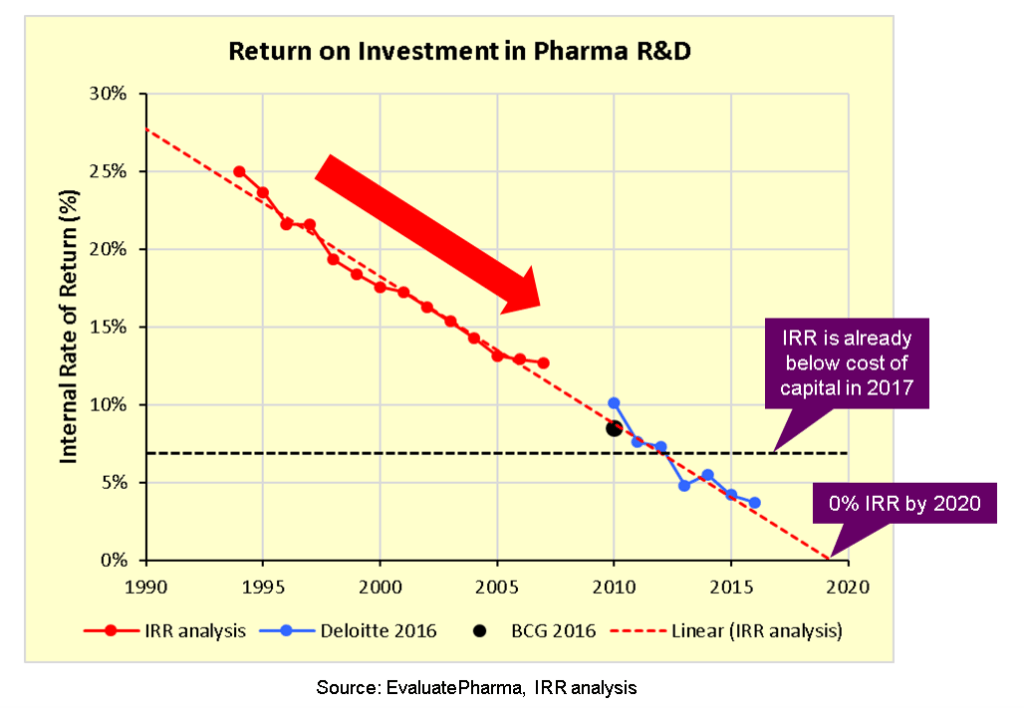

Spanning from the treatment of pneumonia and arthritis to the treatment of infection and cancer, pharmaceutical Research and Development (R&D) has led to incredible medical advancements which immensely improved quality of life and survival rates for those diagnosed with serious medical conditions. As lifespans grow, medical costs continue to rise, with spending on drugs in the US alone expected to reach $590 billion by 2020.(1) However, given the difficulties of maintaining the pace of medical advancements, especially given that “only one of ten compounds that enter human trials ever results in an FDA approval”(2), R&D costs represent a significant investment for pharmaceutical companies seeking to innovate through the creation of new and improved drugs in a competitive and at times saturated market. As recently as 2017, it is estimated that “the top 20 pharmaceutical companies invested 20.9% of top line revenues into R&D”(3). In fact, while gross revenue growth may be increasing, industry experts wonder whether the proverbial well might be running dry, arguing that R&D productivity is on the decline (4) (see Image 1, below). Specifically, comparing data from data engineering firm, EvaluatePharma, with reports published by both Deloitte and BCG, it appears that the Internal Rate of Return for pharma R&D is indeed declining, is “already below the cost of capital, and projected to hit zero within just 2 or 3 years (5). This trend has captured the attention of pharmaceutical companies, which are actively seeking ways to constrain expenses and increase returns.

Image 1: Pharma R&D ROI (6)

As a result, Lilly has launched The Lilly Open Innovation Drug Discovery (OIDD) Program, which links research institutions, academics, and Lilly scientists on a common collaborative platform (7). In addition to mitigating the costs of R&D through distributed innovation, the OIDD program is designed to speed progress in the competitive and rapidly changing biomedical field (8). Currently, Lilly is highlighting the positive impact the collaboration will have, hoping to capitalize on researchers’ inclination and desire to contribute positively to the world. Regarding benefits to researchers, Lilly promises to provide access to their ever expanding databases, tools, and expertise. Specifically, Lilly has developed private libraries of chemically diverse compounds and introduced design tools to create new molecules with groundbreaking properties (9). This partnership takes commitment of resources on Lilly’s part, but offers tremendous upside. Their plan capitalizes on the notion that most biotech and science problems are “potentially amenable to multiple approaches and diverse solutions”, recognizing the potential value in “applying a physics solution to a chemistry problem” (10). In the short and medium term, Lilly sees immense potential in harnessing the power of collaboration of industry with the fields of science and the world of academia.

From a researcher’s perspective, the idea of partnering with a multinational pharmaceutical company like Lilly has both its benefits and drawbacks. In the near term, Lilly needs to address fears the community may have with protecting and preserving their Intellectual Property. In addition, to get this program off the ground, Lilly will need to build momentum by creating some small “victories” and highlighting those to the community, demonstrating the viability of this concept. Cash prizes are certainly a viable option for generating interest in collaboration, but may not necessarily attract those with a similar goal of positive global impact. However, for more sustainable generation of participation in the program, particularly if the platform is not succeeding initially, Lilly must assess both the intrinsic and extrinsic reasons for participation. Specifically, the extrinsic factors including “job market signaling and skill and reputation building” will play a critical role in garnering sustained interest and participation (11). This seems particularly true given their target audience includes both academics and scientists, who will value their ability to experiment and write research on their findings. In the medium-term, Lilly should look to develop a virtuous cycle where the cross-side network effects allow the benefits of participation to drive the benefits to Lilly, which can better fund and incentivize further participation (and so on).

Despite the promise that open innovation holds to speed progress and reign in increasingly costly (and decreasingly effective) R&D, we must realize that Lilly’s OIDD program may prove ineffective, particularly because the start-up costs are relatively high and the benefits may not be realized for decades. At some point, Lilly may decide that the technological, legal, and IP costs associated with starting such a program may outweigh the future benefits. However, given the scale of the potential benefits, is there a role for government intervention in the R&D process, whether in the form of subsidies, tax advantages, sponsorships, or centralization of R&D funding?

(779 words)

Footnotes:

(1) Philipiddas, Alex. “The Top 15 Best-Selling Drugs of 2017.” Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology News. March 12, 2018. https://www.genengnews.com/lists/the-top-15-best-selling-drugs-of-2017/ (accessed November 13, 2018).

(2) LaMattina, John. “Pharma R&D Investments Moderating, But Still High.” Forbes. June 12, 2018. https://www.forbes.com/sites/johnlamattina/2018/06/12/pharma-rd-investments-moderating-but-still-high/#410518f76bc2 (accessed November 13, 2018).

(3) LaMattina, John. “Pharma R&D Investments Moderating, But Still High.”

(4) Stott, Kelvin. “Pharma’s broken business model: An industry on the brink of terminal decline.” Endpoints News. November 28, 2017. https://endpts.com/pharmas-broken-business-model-an-industry-on-the-brink-of-terminal-decline/ Accessed November 13, 2014.

(5) Stott, Kelvin. “Pharma’s broken business model: An industry on the brink of terminal decline.”

(6) Stott, Kelvin. “Pharma’s broken business model: An industry on the brink of terminal decline.”

(7) Lilly. “Open Innovation Drug Discovery” https://openinnovation.lilly.com/dd/index.html Accessed November 13, 2018.

(8) Lilly. “OIDD in Action.” https://openinnovation.lilly.com/dd/oidd-in-action/ Accessed November 13, 2018.

(9) Lilly. “What we Offer.” https://openinnovation.lilly.com/dd/what-we-offer/ Accessed November 13, 2018.

(10) Lakhani and J. Panetta. The principles of distributed innovation. Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization 2, no. 3 (Summer 2007): Page 102.

(11) Lakhani and J. Panetta. The principles of distributed innovation. Page 103.

I think it would be difficult for a government to specifically subsidize Lily’s program, but there may be an opportunity if Lilly can create a consortium of open innovation programs with other pharmaceutical companies. One slightly relevant example is GHIT, which is a program funded by the Japanese government to facilitate a group of pharmaceutical companies, academia, and individual researchers to collaborate in developing drugs for neglected tropical diseases.

I agree that the potential for intellectual property to be illegally disseminated poses a significant risk for Lilly. I question whether anyone would feel comfortable contributing to this platform without more stringent safeguards in place. Even if they want to have a positive global impact, they may worry that research could be warped or exploited by a third party. I also wonder how someone who contributes an idea to this open innovation platform would be compensated if Lilly moves forward with an actual trial and eventual drug. Would they utilize royalties? Who would own any patents developed from this platform? In an industry ruled by valuable IP, Lilly needs to develop more structured IP protections to gain the trust of the scientific and academic communities.

Great point, Lindsey! You may find this article interesting in relation to your comments and questions: https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1537&context=jbl

The challenges that you point out are very relevant. I think that Lilly’s OIDD platform is a great step forward to try and counter some of the decline they have been seeing in their R&D, however there are many hurdles left to overcome on this journey. The biggest challenge that stood out to me has to do with the sensitivities around IP. To build on what @Lindsey Macleod has posed in her comment – what would be “fair” in terms of monetizing any drug discoveries that occur as a result of the OIDD platform? I found this article to provide an interesting discourse on the push-and-pull that has been described: https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1537&context=jbl

Nice piece. It was interesting reading about a pharma company doing open innovation. As mentioned, I can clearly see the challenges to implement open innovation: IP, confidentiality and regulation. I also wonder if, similar to another piece about NASA, scientist in this industry that are super specialized, would feel threatened or undervalue by the implementation of such initiatives.

The intellectual property question is an interesting one for ultimately judging if this program has legs. As a comment from Lindsey above points out, structured protections for valuable IP are important for accessing the scientific and academic communities. There is industry precedent for collaboration between pharma companies and academic researchers, but many of these instances include co-ownership and royalties, providing much more future upside to the researchers. Naturally, the Lilly program seems like a potential boon to the Company given “cash prizes” are likely a relative low cost of product acquisition, though it comes with a shorter term outlay. Will researchers bite?

Interesting read! Yes, while this idea sounds great in bringing a lot of value to an industry that is becoming increasingly costly, I would be concerned about the validating healthcare information that comes from collective sources. Additionally, as mentioned above, issues around confidentiality and regulation are challenges that I believe the industry needs to overcome or find solid solutions for for this to succeed.

Healthcare is plagued by high costs. This is especially true in the pharma industry, and we’ve seen more and more instances of bad actors taking advantage of the system. However, this all makes sense in the context of massive R&D spend that goes into the development of such drugs. This is where I think the OOID Program at Lilly has major upside – by utilizing the power of external forces (i.e. minds) to continue to drive innovation in big pharma. I would emphasize the risks highlighted above as well – IP is a major issue. Not only that, but also the regulatory / accountability aspect of drug development – my main question being: If you don’t have full control / accountability over product development (as I would argue the case is here to some extent), are you opening yourself (Lilly, in this case) to incremental liability / exposure that could potentially have negative consequences – e.g., major fines and PR risk?

Interesting read and you raise great questions. To me, the economic viability of crowdsourcing is still not apparent. First, the future cash flows are diminished if a Company must share its royalty stream with the crowdsourcee. This is particualry true in the pharmaceutical industry where high, volative upfront R&D costs are paid back over a long, stable period of time. Second, the upfront costs, as you mentioned, are high to get a Crowdsource program up and running. Finally, that leads me to believe that if we expect pharmaceutical companies to continue to research and produce drugs, some sort of government intervention will need to occur – a company will not rationally pursue negative IRR projects.

Lilly brings hope for people with conditions that are currently untreated. Scientists with interests that are underfunded will be able to galvanize social support. Researchers who otherwise may not have found each other will be able to collaborate and find solutions. In a time when “big pharma” is a dirty word, this helps show Lilly as a corporation with a heart.

Fascinating article. As Svernadi mentioned, demonstrating the efficacy of the OIDD programme is critical to ensuring its long-term viability. However, given the difference in the nature of a traditional sequential model of early drug discovery R&D, it is not clear that usual models of assessing R&D productivity, focused primarily on economic returns, would be the best approach here (1).

Carroll et al., propose a balanced dashboard of leading and lagging indicators across four categories to assess the success of an open innovation approach. These include investment, returns (in terms of hypothesis tested, new research conclusions etc.), pipeline health and culture & capabilities.

Across these categories, the OIDD program, as assessed in 2017, compares favourably with more traditional R&D programs. It has generated over 1.8m datapoints as a result of the testing of almost 50,000 crowdsourced compounds, yielding ~4% actives across projects – a comparable success rate to typical early drug discovery programs for an investment of $150 per compound (1).

Hopefully, this combination of a balanced view of assessing the success of open innovation R&D programs and the promise shown by programs such as Eli Lilly will encourage more biopharmaceutical companies to embrace open innovation.

1. Carroll GP, Srivastava S, Volini AS, Piñeiro-Núñez MM, Vetman T. Measuring the effectiveness and impact of an open innovation platform. Drug Discov Today. 2017 May 1;22(5):776–85.

Great article!

Before reading I was extremely skeptical about the potential for Open Innovation in healthcare. Given the immense regulation that governs the healthcare space, I struggled to see how industry could leverage open innovation to advance R&D efforts.

After reading, my perspective has completely changed. I now see how it is sensible for a company, such as Eli Lily, to partner with a leading researcher/academic to develop the next breakthrough drug. With the diminishing returns that pharmaceutical R&D now delivers, it is logical to see pharmaceutical companies opening up their R&D efforts.

I am convinced Open Innovation will help advance the quality of healthcare in the future. But if competitors begin to do the same, can Eli Lily ensure/retain a competitive advantage in this open landscape?

As many people have pointed above, I think the idea of open innovation is great, but Lilly must be very careful with how they interact with the collaborators. In addition to the question of compensation, how should Lilly interact with collaborators when the process approaches more “sensitive” points such as the need for trials? Does Lilly conduct the trials itself? If Lilly is at any point being perceived as taking unfair advantage of collaborators, it could lead to a mass exodus of collaborators from the platform and make it virtually impossible to recoup the initial set-up costs for the platform. I love the idea of open innovation, but I wonder how difficult it is to properly incentivize people on all sides to actively participate in a for-profit setting.